Selections from the SAR Museum Collection

By: Zac Distel

Note: A shorter version of this article originally appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of the SAR Magazine.

The SAR is now the proud home of two Revolutionary War era swivel cannons, one iron and one bronze, thanks to donations by SAR members to the Museum Board’s Artifact Donor Program. A swivel cannon (or gun) is a weapon larger than a musket and too heavy to fire unsupported, ranging in size from a heavy musket to a small cannon with a 1-2 inch bore. American furnaces, mills, and foundries scrambled to manufacture cannon of all sizes for the American Revolution. Patriot craftsmen produced a limited number of battle-ready bronze ordnance, but broader familiarity with iron allowed one foundry to cast 3,000 small cannons during the war. Bronze was desired above iron for several reasons including its greater ability to withstand pressure thereby reducing the quantity and weight of material needed to produce a cannon, when a bronze cannon did fail it tore rather than fragment which was less dangerous, and non-ferrous bronze did not rust. Iron cannons did, however, excel over bronze in some regards as it did not heat up as quickly in battle, iron had a longer lifespan, and iron was more cost-effective to produce with bronze being eight to nine times more expensive.

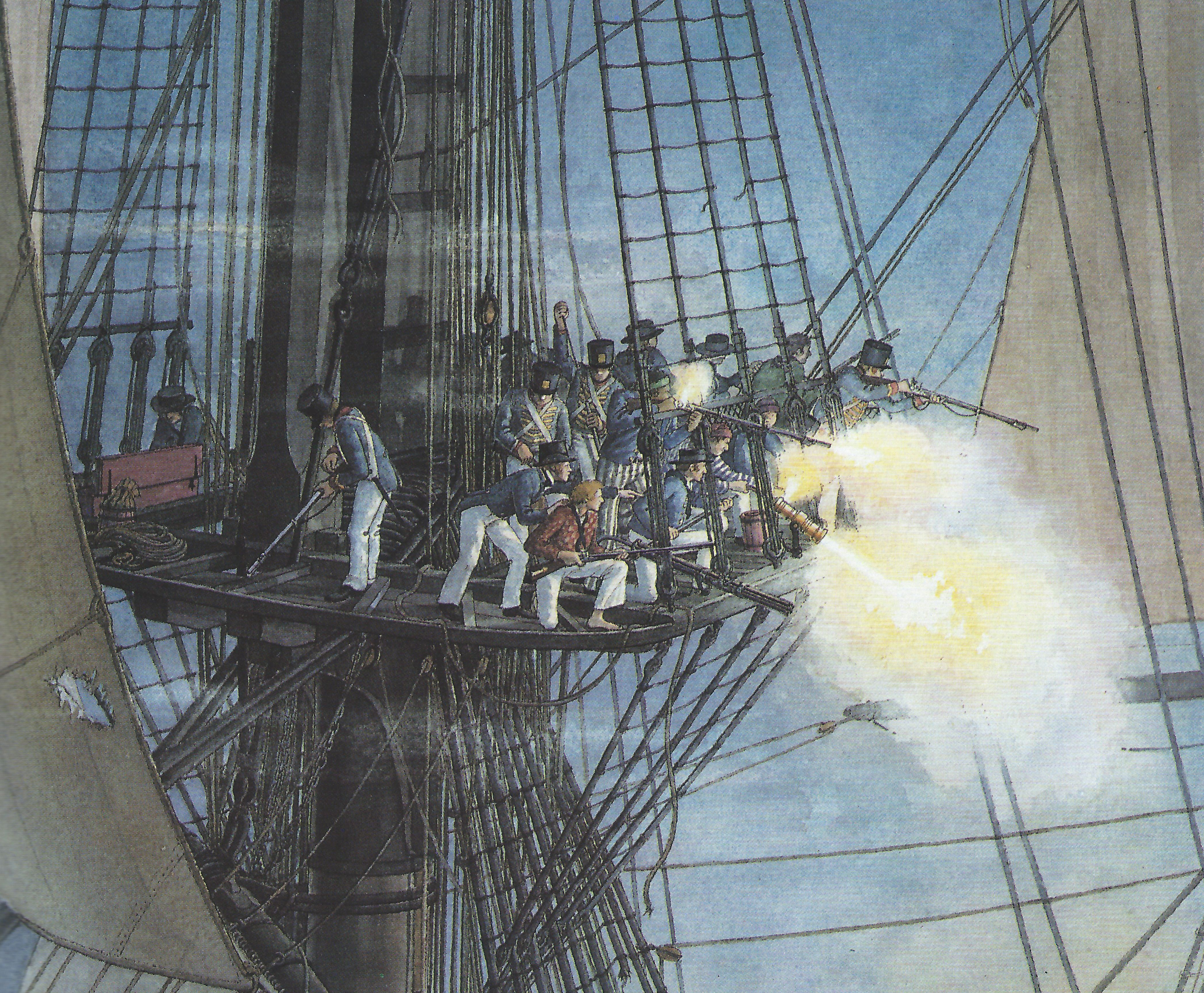

Swivel cannons were widely used throughout the colonial period and the American Revolution. Whether mounted on a frontier fort’s rampart or a ship’s gunwale, swivel cannons were a powerful anti-personnel weapon that fired musket balls, grapeshot, and langrage (mixture of scrap iron, broken glass, shot, etc. considered indecent for respectable 18th century warfare). Larger vessels equipped with a maintop platform, sometimes called a “fighting top” if purpose built, would place swivel cannon at that elevated position allowing crew to fire down onto the decks of opposing ships (see fig. 1).

Merchant and privateer vessels that were unable to obtain swivel cannon sometimes used what were called “Quaker” guns—wooden cannon painted and positioned to bluff an enemy. Lacking bronze or iron swivel cannon to defend Fort Boonesborough during a siege in 1778, Squire Boone devised two made of hollowed-out gum tree logs wrapped in iron bands. Although they only fired a handful of times before cracking, Boone’s wooden swivel cannon dispersed a group of Native American and British attackers.

With an acorn shaped cascabel (rear protrusion), the SAR’s iron swivel cannon is a traditional American pattern and lacks proof marks (see fig. 2). This bronze swivel cannon does not bear such distinct design features, but the lack of proof marks and relatively crude finish are indicative of American manufacture (see fig. 3). These two swivel cannon will be treasured artifacts for the SAR Education Center & Museum, Outreach Education interpretations, and public programming. They are evidence of late 18th century American industrial ingenuity, the ferocity and real human cost of the war, and the immense resources and effort required to meet just one military need of the Revolution. After arriving in January 2020, the SAR’s bronze swivel cannon was cleaned and waxed by staff; the same level of conservation is slated for the iron swivel cannon.